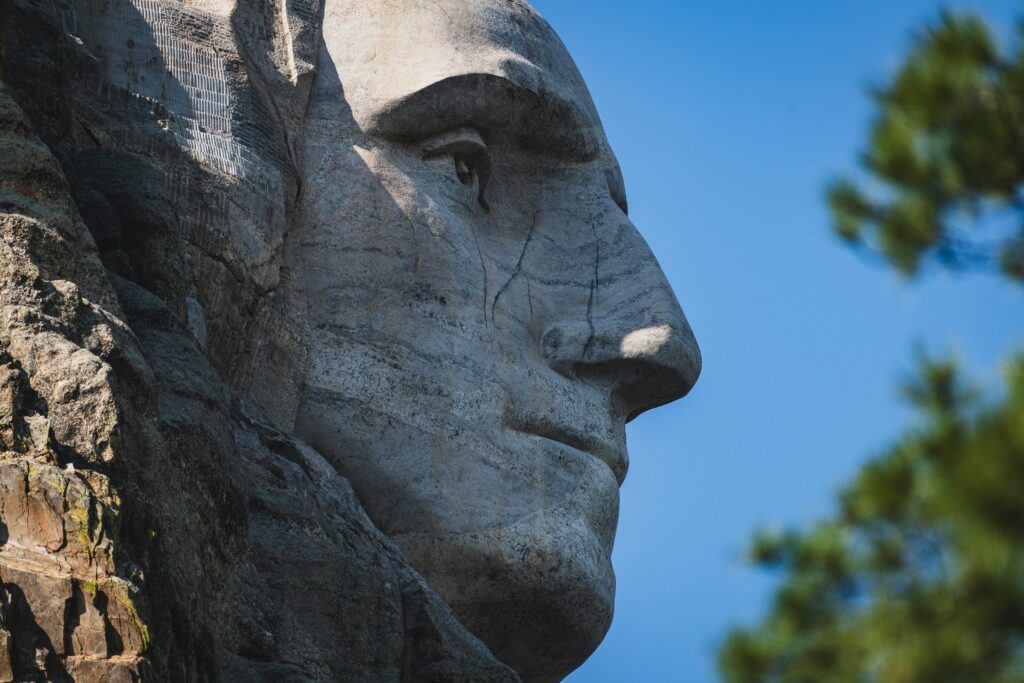

Jon Sailer, Unsplash

Jon Sailer, Unsplash A need to reinvest in civics education has become a bipartisan refrain in recent years. While academics lament declining trust in our institutions and worsening political polarization, civics education has become an often-invoked panacea. But civics has also become a front line in the ongoing culture wars. Liberal faculty suspect high-profile civics initiatives at the University of Florida, the University of Texas-Austin, and Arizona State University of corroding academic freedom and creating “conservative DEI” programs on campuses across the country; meanwhile, a recent $1 billion congressional plan to boost civics education fell victim to conservative opposition.

Institutions that embrace civics education can stanch declining enrollments and reclaim their faltering reputations among Americans. Civics education alone cannot solve the complex problems facing American society. But institutions of higher education that embrace civics education can stanch declining enrollments, reclaim their faltering reputations among Americans, and contribute to a revival of the country’s civic health. As more colleges and universities experiment in the civics space, an untapped resource lies in wait: partnerships. Partnerships with institutions already invested in civics education are an open frontier in higher education. Such partnerships open up new learning environments, build bridges across disciplines, model bipartisan engagement, and shepherd students to a new arena of employment we call “civics careers.”

Given the great diversity of organizations and actors now entering the civics game, it is important to find the right partner. Leading civics groups have stated that collaboration is key to the civics-education ecosystem, but, given the great diversity of organizations and actors now entering the civics game, it is important to find the right partner. Civics coalitions have come into vogue in recent years, with brand-name institutions and prominent educational leaders pledging alliances that commit diverse signatories to lofty goals for improving civility and knowledge of governing processes.

Coalitions are certainly an important driver of success in the civics space, but they leave room for significant variation in how signatories promote the civic health of the United States. Notably, there remain serious differences between “action civics,” favored by progressive groups, and civics rooted in patriotism and the acquisition of a deeper understanding of Western civilization and first principles, preferred by conservatives. Few partnerships bridge political differences in the development and cooperation of an accredited civics curriculum and educational experience. More universities should consider presidential foundations, which have grown more unified in their efforts to protect democracy and have emerged as ideal partners in civics education.

The Academy for Civic Education and Democracy (ACED) models this type of partnership. Launched in June 2024 by George Washington University (GWU), through a collaboration of its Graduate School of Political Management and the Elliott School of International Affairs with the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute (RRPFI), ACED exemplifies the path to partnerships for civics education. Civics-education partnerships are a potent tool for colleges and universities striving to overcome their credibility problem in the sector.

Recent findings from the Chronicle of Higher Education show that, while 68 percent of Americans believe the development of a well-informed citizenry should be considered one of the most important functions of college education, only 31 percent of Americans overall believe colleges are doing a good job—and college education suffers from a dismal 24-percent approval rating from conservatives. In the case of ACED, GWU’s relationship with the RRPFI made a big difference: 85 percent of surveyed students saw the partnership between a nonprofit representing the principles of conservatism’s most iconic president and a university committed to bipartisanship as a factor that enhanced the attractiveness of the program.

Getting serious about civics education means getting serious about placing students in civics careers. Summer programs such as ACED that guarantee internship placement on Capitol Hill, in policy-engaged nonprofits and think tanks, in lobbying and PR firms, and at other civic-minded organizations are critical to creating a pathway for students into civics careers. Workplaces in particular, according to a new report from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, are seen by most Americans as a bastion of civility in an otherwise uncivil society.

The push toward civics careers will help assuage one of the main challenges facing civics education in higher ed, which is that many universities have evolved to market their collegiate experience as four-year career-training programming rather than a process of developing critical thinkers and lifelong learners. Students’ aspirations for high-paying “STEM careers” contributed to the redistribution of majors on college campuses that put liberal-arts departments traditionally associated with higher rates of civic engagement in a state of terminal decline. No analogous push to promote high-impact and high-paying “civics careers” emerged to bolster the prospects of the liberal arts. Linking internships to the curriculum with the goal of developing a toolkit for civil dialogue is an essential component of civics education. Building professional ties that strengthen partnerships between foundations, think tanks, and universities will drive home the reality that civic learning happens inside and outside of the classroom.

The promise of civics education cannot simply lie in the aspiration of making students better citizens; it must be complemented by professional opportunity. But the promise of civics education cannot simply lie in the aspiration of making students better citizens; it must be complemented by the promise of professional opportunity. Civics careers are one side of the professional equation; further study is the second. Civics education can become an explicit focus of graduate education. Partnering with a graduate-school program, such as George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management, creates a valuable pipeline for the university and students alike.

Linking internships to the curriculum is an essential component of civics education. The crisis of civic health in the United States requires a full mobilization of resources, both public and private. Two related issues have constrained the impact of the ongoing mobilization effort. First, civics has historically been a regional phenomenon. The energy and money associated with the renewed focus on civics education in higher education has largely come through initiatives at flagship red-state universities that primarily service in-state students. A summer program in the image of ACED, which in 2025 enrolled students from 35 colleges and universities across the United States, both public and private, breaks past the regional dynamics that have long defined American politics. However, summer civics programs in Washington, D.C., need to persuade students and faculty alike that they are not a substitute for major civics initiatives on college campuses but a capstone to curricula that run the course of the standard academic year.

Along with geographic diversity comes ideological diversity, which leads into the second advantage of a summer program that follows the model of ACED: intentional recruitment of ideological diversity. While the curation of experiences that expose students to different viewpoints is often the focus of civics initiatives, the actual selection of participants, as well as the general environment set by program staff and partners, is worth highlighting. The admissions process, from recruiting to application review and decisionmaking, should be guided by a shared understanding between partners that GPA is not a core determining factor. Instead, demonstration of active engagement at a student’s home campus or in his or her community, as well as openness towards working and learning across differences as outlined in the form of an essay, should drive the admissions decision. Heterogeneity in the student cohort in terms of location and viewpoints should be encouraged, but homogeneity in terms of interest to engage with each other is essential.

Commitment to these goals requires scholarships. Presidential foundations, which capture a donor pool that is distinct from most colleges and universities, are a particularly attractive option for universities searching for partners to combine resources to offset the cost of civics education. In the case of ACED, this allowed for over 95 percent of ACED students to receive a scholarship of an average value of 60 percent of total program cost.

Colleges and universities occupy a central place in the civics landscape of the United States, but their collective mission does evolve over time. From their origins in religious education, to post-WWII workforce development, to modern attempts at middle- and upper-class diversification, universities have been historically much more responsive to changes in America’s political realities and social fabric than many have come to believe. Partnering with an institution whose core mission is civic engagement can focus higher education on rebuilding civic knowledge.

RRPFI and GWU have modeled this partnership in ACED by embracing Reagan’s farewell call to nurture an “informed patriotism” and Washington’s final warning against partisanship. As this wave of populist backlash crashes against higher education, and institutional leaders strive to shore up support, partnerships with civics-focused institutions can create a pluralistic new chapter on American campuses. For the sake of education and civics alike, we hope American colleges and universities can rise to the opportunity. Presidential foundations and other partners will await the call.

Anthony Eames is director of scholarly initiatives at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute. Tobias Greiff is associate dean for academic affairs at the College of Professional Studies’ Graduate School of Political Management at George Washington University. Jacob Bruggeman is a Ph.D. candidate in history at Johns Hopkins University.